Baker City man leading effort to stop nation’s biggest wildfire

Published 2:28 pm Friday, July 23, 2021

- The Bootleg fire, burning in Klamath and Lake counties, is the biggest blaze in the nation.

Joe Hessel remembers when the Dooley Mountain fire, which burned 20,000 acres south of Baker City over several days, was a “giant” blaze.

Trending

Today he’s coordinating the effort to stem a fire that burned more land than that every day.

For almost two weeks straight.

This yawning difference between what was typical early in Hessel’s career, and what is commonplace today, illustrates his longevity in a way perhaps more compelling than a couple of numbers can.

Trending

Certainly Hessel, who lives in Baker City and is in his 38th summer amidst the smoke and the flames, can attest to the changes time has wrought when it comes to fighting wildland fires in Oregon and across the West.

The Dooley Mountain fire, sparked by lightning in late July 1989, was at the time the biggest blaze in Baker County in several decades.

It was also an abnormally large fire by Oregon standards.

But today, the acreage charred that distant summer would occupy a scarcely noticeable corner of the fire that has kept Hessel away from his Baker City home, and his La Grande office, for almost two weeks.

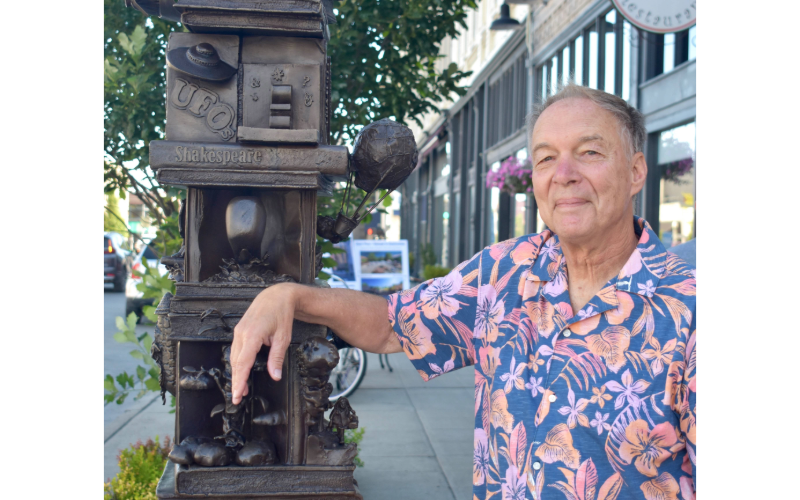

Hessel, 54, who is the Northeast District forester for the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF), is one of three incident commanders for the Bootleg fire, a lightning fire burning in Klamath and Lake counties in south-central Oregon.

At 400,000 acres as of Thursday, July 22, it’s the nation’s biggest blaze, the one responsible for much of the smoke that has clogged Baker Valley at times this month.

The one that has spawned smoke plumes which look, from the vantage point of space satellites, similar to a cataclysmic volcanic eruption.

Hessel said his experience on the Bootleg fire has led him to ponder, as he sometimes has over the past 32 years, the days when he worked on the Dooley Mountain fire as a firefighter with the ODF.

“That was one of the first big fires I was involved in, and it left an impact on my mind,” Hessel said in a phone interview on Wednesday, July 21 from the Bootleg fire camp.

The Dooley Mountain fire affected Hessel in a couple of ways.

He remembers vividly the photograph that S. John Collins, retired Baker City Herald photojournalist, took from Main Street in downtown Baker City on July 30, 1989. The photo shows the fire’s smoke cloud looming above the city’s historic buildings, the angle of the lens making the blaze seem much closer than it was (the fire never got within about eight miles of town).

Hessel calls the photo an “iconic image.”

But that acreage figure — 20,000 — was memorable, too.

In 1989, its size made the Dooley Mountain fire an outlier.

It was a time when firefighters considered even a 500-acre fire a significant blaze.

But then Hessel, who started his firefighting career with ODF at age 16, compares Dooley Mountain to Bootleg.

“This fire grew an average of 30,000 acres for 13 days straight,” he said.

The Bootleg fire is the sort of blaze that requires a group of specialists — what’s known as an “overhead team” or “incident management team” — to coordinate the efforts of hundreds or even thousands of people, as well as bulldozers and other equipment on the ground, and air tankers and helicopters above.

Almost 2,400 people were assigned to the Bootleg fire.

Hessel, who heads one of the ODF’s three overhead teams, said they have been called out more often, and for longer periods, over the past several years.

He said it has become increasingly difficult for agencies to find employees willing to potentially give up much of their summer, to forego family vacations in favor of traveling hundreds of miles to work on a big blaze.

“We used to go out maybe only once in a summer,” Hessel said. “One of our teams was out five times last year.”

The Bootleg fire is his team’s second assignment this summer. The first, also in Klamath County, was the Cutoff fire in June.

Hessel, whose dad was a Forest Service smokejumper and manager of the firefighting air center in La Grande while he was growing up, said incident management teams typically are assigned to a fire for 14 days, with the potential to extend the stay to 21 days.

Team members then return home for a couple days.

Hessel, who was sent to the Bootleg fire on July 10, said he doubts he’ll return home before July 27.

And after his time off, he said his team will be “back on the board” — meaning they’re available to be assigned to another fire.

And with most of Oregon enduring extreme fire danger, Hessel doesn’t expect to wait long for his next job.

“It’s become a recurring theme every summer,” he said.