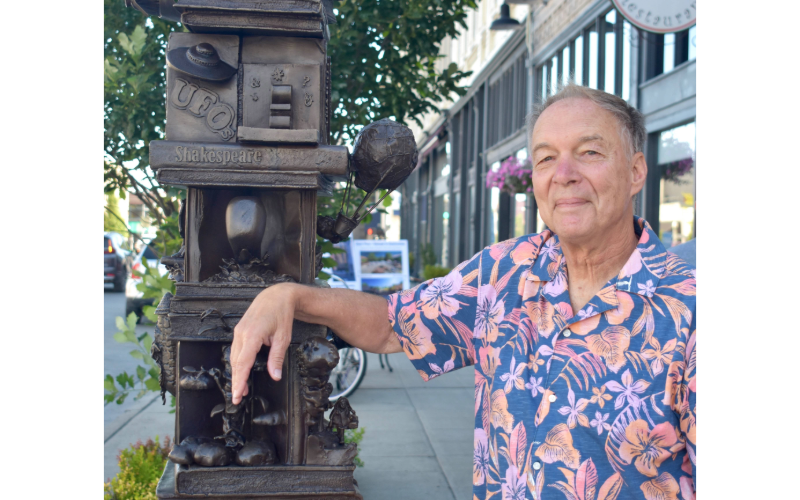

Matt Ward of Baker City mixes determination, technology to play an integral role in his family’s operation despite spina bifida

Published 12:38 pm Wednesday, July 30, 2025

Matt Ward’s climb from his pickup truck to the tractor’s cab is a trifle unconventional — a remote control is involved in the ascent — but once seated he’s prepared to take on the typical tasks of the farmer in the customary way.

The same tasks his father and his grandfather and his great-grandfather have plied in the rich soils of the grand valleys that lie between the Elkhorn Mountains and the Wallowas.

Plucking weeds.

Trending

Smoothing the fields so they’re ready to take seed.

Hoping the showers, never entirely reliable in this arid land of rain shadows, will come when the wheat can best make use of the moisture.

The hours can be lonely, Ward concedes, piloting the John Deere across these empty acres near the base of Ladd Canyon, several miles north of North Powder.

“I like the seclusion, but there are days when I wish I could farm in town,” he said.

There are distractions, to be sure.

An occasional antelope sprints past with its smooth effortless gait.

Trending

Hawks soar across the sprawling sky, riding the thermals.

And when wildlife are absent, there are manmade alternatives.

Ward gestures to Interstate 84, less than a mile to the west.

“There’s the freeway traffic to keep me awake,” he says with a smile. “I like to watch Oregon State Police pull people over. That’s my entertainment.”

Then there’s this tractor. It’s an altogether different machine from the ones his grandfather, Ralph Ward, drove.

(To say nothing of his great-grandfather, Clyde Ward, who relied on literal horsepower rather than the petroleum-fueled sort.)

He points to the AM/FM radio perched above the air-conditioning controls.

And of course he has his cellphone.

“I call people — or they call me,” Ward says.

But the tractor’s heated and cooled cab, its stereo speakers, aren’t the things that distinguish it.

Ward can run this powerful machine, dragging all sorts of implements behind its four head-high rear tires, by using only his two hands.

As, indeed, he must.

Ward, 30, was born with spina bifida.

His legs can’t support him.

Although he can move his left leg slightly, something he demonstrates and then immediately apologizes for after his cowboy boot grazes a visitor’s leg who sits beside him in the cab.

“Sorry for kicking you,” Ward says.

This tractor, which came equipped with hand controls, has done much more than make it possible for Ward to look after these 450 acres that grow dryland winter wheat, the part of his family’s operation farthest from their headquarters in Baker City, 25 miles or so to the south.

This machine, and others like it, have helped transform Ward from a member of the fourth generation of his family to farm in Baker and Union counties, to something else, something to him infinitely more meaningful.

It helped make him a farmer.

“I would say my confidence level has gone up significantly in the past 10 years,” Ward said. “My dad has put a lot of trust in me. This has been my domain.”

Dad is Mark Ward. Mark and his brother, Craig, oversee the operation that their grandparents, Clyde and Leonora Ward, started in the early 20th century and that was continued by Clyde and Leonora’s children, Ralph, Alvin and Charlotte. Mark and Craig are the sons of Ralph and Alice Ward.

(Both Ralph and Alice died in 2023.)

Ward Ranches — the family raised cattle for decades but now focuses on field crops — raises wheat, peppermint, potatoes, alfalfa and field corn.

Matt Ward said he always figured he would be a farmer.

But as he grew up, watching the seasonal sequence of plowing, seeding, irrigating, harvesting, he wondered what his role would be.

“It was definitely frustrating that I couldn’t operate the equipment,” he said. “Growing up it was a struggle. I couldn’t get in a tractor and do a field for my dad.”

But for the past decade or so, Ward has thrived.

Newer tractors, including the John Deere model 7980 he sits in on a hot, sunny morning in early July, are equipped with hand controls.

“This is the first tractor I could drive myself,” he said.

In addition to the hand controls, the tractor has an infinitely variable transmission — a type of automatic transmission that allows the driver to change speeds without pushing in a clutch pedal.

Ward said he can drive other tractors by using rods connected to foot pedals.

“But this is a lot better,” he said.

The tractor is only part of the equation, though.

Ward has to get to the cab, which is nearly as far off the ground as a basketball hoop.

“And I do not like heights,” he says with a smile.

The solution is bolted to the flatbed on Ward’s Ford F250 pickup truck.

The apparatus resembles something a movie crew might use to film a scene requiring an elevated vantage point.

It consists of a hydraulic arm that can move in any direction. Affixed to its end is a shiny steel seat that looks as though it would be as slippery as a cookie sheet.

And, on this nearly cloudless summer day, almost as hot.

“It’s been hot enough that I’ve felt it through the seat of my pants,” said Ward, who is clad in denim overalls and a checkered western shirt.

This seat — equipped with waist and chest belts, both of which Ward eschews — is his ride from pickup to tractor.

He manipulates the seat by pressing buttons on a remote control attached to a lanyard around his neck.

Ward deftly maneuvers the seat until it’s about level with the pickup’s driver’s seat. He boosts himself onto the metal platform and, with the quick and precise movements of a dedicated video game player holding a controller, he elevates himself to the tractor’s door.

He clambers onto the air-cushioned seat inside the cab with a carefree ease that betrays long practice.

Ward is ready to spend the next eight hours or so in the field, which fades in the distance to a shimmering mirage as the temperature rises into the 80s.

That’s not a task for today, however.

This field is fallow, on a yearly rotation with another nearby field where wheat is ripening toward harvest in late July or early August.

Ward said his main task this summer is to run the rod weeder through the field occasionally, preparing the ground for seeding this fall.

It takes four days or so to get through the whole of the 450 acres.

And although Ward relishes his autonomy, he also understands the vagaries of farming.

“As much as there are bad days, there are good days,” he said. “I just take the position that you’ll get through it.”

His favorite crop is peppermint.

The Wards’ fields near Baker City sweeten the air with the astringent scent of mint each August, the aroma especially pungent when the distiller is running, concentrating the oil from the harvested plants.

The timing of the harvest, during the dog days of summer, isn’t ideal, Ward admits.

“Harvest time is hot,” he said.

But as with all the jobs that a farmer confronts, it has to be done, come scorching heat or drenching downpours.

And Ward, aided by technology but driven mostly by his own ambition, is happy to have the chance to carry on the tradition that in his family is well into its second century.

“Knowing that I get something done, and that I feel confident about doing it.”