The Blues Beckon

Published 1:33 pm Friday, January 22, 2021

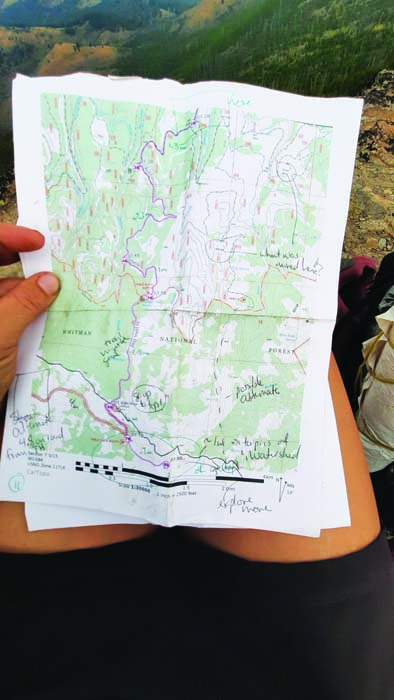

- Renee Patrick kept detailed trail notes during her hike to help Jared Kennedy, Blue Mountains Trail coordinator for the Greater Hells Canyon Council, assemble an online guide to the 566-mile route.

Renee Patrick started her epic walk through the Blue Mountains in the sweaty heat of July, and she finished it amid the nostril-freezing chill of an alpine autumn.

Along the 566 miles of hiking in between, Patrick was at turns challenged, enlightened and even awed by the eclectic landscapes of Northeast Oregon.

She also made history.

And now, a few months after she finished her trek, Patrick is helping to promote the Blue Mountains Trail, a route she and other proponents hope will join the ranks of America’s other long-distance wilderness paths.

“It’s fun to be at the beginning of an effort like this that people are excited about,” Patrick said in a Jan. 14 phone interview. “It’s exciting for the eastern half of the state to have more recreational opportunities. Northeast Oregon is not well-known, even by a lot of Oregonians.”

Although the current version of the Blue Mountains Trail is new, the concept dates back more than half a century.

Loren Hughes, a longtime La Grande jeweler who died on Jan. 29, 2016, envisioned a long hiking route through the Blue Mountains as far back as 1960.

Later, Hughes and Dick Hentze, who taught elementary school in Baker City from 1970 to 2000, conjured the idea of the Blue Mountain Heritage Trail.

Hentze, who moved from Baker City to the Eugene area in 2014, died on Aug. 8, 2020.

Mike Higgins of Halfway said in a Jan. 14 interview that he became involved with planning the trail in the 1990s along with Greg Dyson, director of the Hells Canyon Preservation Council.

(The organization, based in La Grande, was renamed as the Greater Hells Canyon Council in 2017, its 50th anniversary.)

“The route was much different then,” said Higgins, an advisory board member for the Greater Hells Canyon Council.

The previously proposed trail was a loop that covered about 870 miles.

Among the notable differences, the current route — the one that Patrick helped pioneer with her hike in the summer and fall of 2020 — is point to point rather than a loop, with Wallowa Lake State Park at the northern end and John Day at the southern.

“The current route to me is a lot more attractive,” Higgins said.

In particular, he appreciates that the Blue Mountains Trail passes through all seven of the federal wilderness areas in Northeast Oregon — Eagle Cap, Hells Canyon, Wenaha-Tucannon, North Fork Umatilla, North Fork John Day, Monument Rock and Strawberry Mountain.

Higgins said he believes this concept, so long in the making, finally has momentum.

“I think it’s going to go this time,” he said. “Jared is going to make sure it goes.”

Jared in this case is Jared Kennedy.

He’s the Blue Mountains Trail project leader for the Greater Hells Canyon Council, a task that includes maintaining the trail’s website, https://www.hellscanyon.org/blue-mountains-trail

“This is an opportunity for people to get a much better idea of the landscapes of the Blues,” Kennedy said in a Jan. 14 interview. “It really ties the region together.”

But when it comes to connections, no amount of conceptual planning or pondering of maps can replace the actual experience of hiking the route, Kennedy said.

That’s why the efforts of Patrick and a separate group of three hikers were so vital.

That trio — Whitney La Ruffa, Naomi Hudetz and Mike Unger — hiked the entire Blue Mountains Trail during September.

Patrick said she exchanged information with the three other hikers about their experiences, particularly any problems they encountered with navigation, distances between water sources and other matters important to future hikers.

Now that four people have negotiated the route, Kennedy said he has a much better idea of the trail’s attributes — and its problems.

Although it’s called a trail the route does include several sections on Forest Service roads, although most of those are little-traveled roads in remote areas, Kennedy said.

There are no plans to propose the construction of any new trail, he said.

With so much new data to digest — including GPS waypoints and other digital details — Kennedy is striving this winter to make the trail’s website more informative.

His goal is to have an online guide for hiker-ready sections of the Blue Mountains Trail, including maps, by spring, in time for the prime hiking season.

Solo hiker’s experiences

“Prime” not necessarily being a synonym for “perfect” in this case.

Kennedy points out that the window for hiking the entire Blue Mountains Trail is a relative small one, although he acknowledges that the vast majority of hikers will only attempt sections rather than trying to cover all 566 miles in a single trip or even a single year.

The reason is elevation.

The trail samples each of the higher ranges of the Blues, including the Strawberrys, Elkhorns, Greenhorns and Wallowas. Sections of the trail in those areas climb well above 7,000 feet, and in places are reliably free of snow only during August and September.

Yet the trail also descends into Hells Canyon, where summer temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees.

Given that even an experienced long-distance hiker is likely to need 30 to 45 days to complete the entire trail, a start in July or early August would be the most plausible, both to avoid deep lingering snowdrifts from the previous winter, and the first storms of the next.

But a midsummer start has its own potential challenges, as Patrick discovered.

She began her journey at John Day in August. The temperature was 99 degrees. And the first day included a stint on a freshly blacktopped road (a rare paved section) and a 4,000-foot climb over 7 miles, among the more difficult ascents of the entire route.

Patrick said she took a break during the hottest part of that day and finished the climb in the comparative cool of the evening.

Her schedule allowed her to hike for only a week in August. She covered the 110-mile section from John Day to Austin Junction, where Highways 26 and 7 meet, about 50 miles southwest of Baker City.

Although that’s a longer trek than most hikers will ever attempt in a single trip, it’s little more than a jaunt by Patrick’s standards.

Few people can match her hiking resumé.

Patrick has thru-hiked — completing an entire trail in one year — America’s “triple crown” of long-distance routes, the Pacific Crest, Appalachian and Continental Divide trails.

The cumulative mileage of that trio of epic trails is about 7,800 miles — 3,100 miles for the Continental Divide Trail, 2,610 for the Pacific Crest, and 2,100 for the Appalachian.

Patrick also helped to pioneer the Oregon Desert Trail in the state’s remote, sagebrush-dominated southeast corner. She hiked the 750-mile route in 2016, the year after she was hired as Oregon Desert Trail coordinator for the Oregon Natural Desert Association in Bend, where she lives.

At 566 miles, the Blue Mountains Trail isn’t terribly daunting for a hiker with as many miles on her boots as Patrick.

But she said every route, regardless of distance, brings its unique challenges.

The Blue Mountains Trail, unlike the well-known and generally well-maintained Pacific Crest and Appalachian trails, includes several stretches that require hikers to “bushwhack” — find their own way across trailless (and roadless) stretches.

And although many of the trails and roads that comprise the Blue Mountains Trail are individually signed, there are no markers for this new trail itself.

“People need to be realistic about the challenges,” Patrick said. “It’s a great trail for section hiking, as a way to build your skills.”

Higgins, who helped La Ruffa, Hudetz and Unger during their thru-hike by meeting them at trailheads with boxes of food and other supplies, pointed out that the Blue Mountains Trail, because it is made up of so many existing trails and roads, has a multitude of access points.

And it features some sections that are easier to hike than others, such as the Elkhorn Crest National Recreation Trail west of Baker City.

“You can select sections that match your skill level,” Higgins said.

Regardless of where you hike, though, you’ll be surrounded by some of Oregon’s most spectacular scenery, Patrick said.

Among the sections that especially entranced her is through the Eagle Cap Wilderness south of Wallowa Lake. That’s where she started her second and final stint on the trail, in early October.

The Blue Mountains Trail follows the West Fork of the Wallowa River to Frazier Lake, then crosses Hawkins Pass and descends to the headwaters of the South Fork of the Imnaha River.

“I absolutely loved hiking in the Eagle Cap,” Patrick said. “That’s really an awesome section.”

She also appreciated that the route allowed her to trace a major river — the Imnaha — nearly from its headwaters below Hawkins Pass to its mouth at the Snake River in Hells Canyon.

The Blue Mountains Trail affords the hiker a similar experience with the Grande Ronde River.

“When you see it from the start to where it ends you almost have a relationship with the river,” Patrick said. “I really enjoyed that.”

The Blue Mountains Trail is also enticing for both its geology, which includes rocks more than 200 million years old, as well as considerably more recent cultural history.

Patrick said that while she hiked through the ancestral homeland of the Nez Perce tribe, including a section of the Nee-Me-Poo National Historic Trail, she listened to an audio version of “Thunder in the Mountains,” a historical account chronicling the Nez Perce being driven from the area in 1877 as white settlers moved into Wallowa County.

Patrick said the hike into and out of Joseph Canyon, named for Nez Perce Chief Joseph, was probably the hardest section of the Blue Mountains Trail.

Among the other difficult sections were those where wildfires have burned in the past decade or so. That includes what was otherwise one of Patrick’s favorite areas, the Wenaha River Canyon, which she describes as “amazing” and “beautiful.”

“Fire has affected a lot of the trails,” she said. “Every year more trees fall. It’s on ongoing maintenance issue.”

Nor is fire the only threat to some of the trail sections that make up the Blue Mountains Trail, Kennedy said.

“There are many, many sections of trail that are way behind in terms of maintenance,” he said.

Not long before Patrick finished her thru-hike in late October, she hiked the Elkhorn Crest Trail during an early preview of winter when temperatures plummeted into the single digits.

She wasn’t deterred — “I do a lot of cold weather and winter camping,” she said — but Patrick said the range of experiences, from her sweltering start to the frigid conclusion, was appropriate for a trail with so many moods.

Patrick, along with Kennedy and Higgins, hopes this newest addition to the West’s long-distance treks will not only enchant hikers, but also bring an economic benefit to the region.

The route comes close to several towns, including Baker City, La Grande and Enterprise, and Kennedy said local residents and businesses could earn extra money shuttling hikers between trailheads and providing other supplies and services that hikers would need.

Ultimately, though, she said the Blue Mountains Trail is a treasure for people who want to follow in her bootsteps.

“It’s a great opportunity for hikers,” Patrick said.

ABOUT THE ROUTE

A mixture

The 566-mile Blue Mountains Trail includes both existing trails, Forest Service roads and some short sections that require cross-country travel. It is not a single route; there are alternates for certain sections so inexperienced hikers can avoid cross-country travel.

Wilderness wandering

The route passes through each of Northeast Oregon’s seven wilderness areas.

First thru-hikers

Four people hiked the entire Blue Mountains Trail in 2020. Renee Patrick completed the first solo thru-hike. Whitney La Ruffa, Naomi Hudetz and Mike Unger hiked the route together.

The future

The Greater Hells Canyon Council in La Grande is working on detailed maps and route-finding guides. More information is available at www.hellscanyon.org/blue-mountains-trail