Tracking Winter

Published 7:15 am Saturday, December 19, 2020

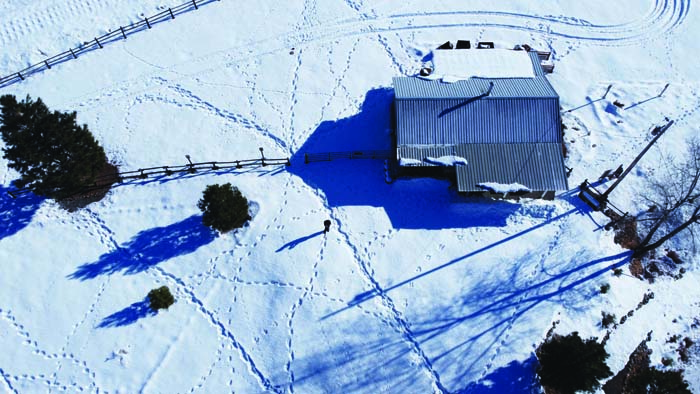

- A view from a drone shows boot tracks in the snow at the Sumpter Valley Dredge State Heritage Area. The building in the upper right is the park visitor center and gift shop, which is closed for the winter.

Beavers are reclusive and elusive, but they can’t do much about that telltale tail.

Trending

The paddle-shaped flap of fat, sinew and muscle will betray the beavers’ presence even though the animals spend much of their time in their lodge or underwater.

The appendage leaves especially conspicuous evidence of its passage when fresh snow covers the ground.

The erosive forces of wind and the freeze-and-thaw cycle can obscure or even erase the marks left by beavers’ paws.

Trending

But the smooth depression made by the tail, reminiscent of a child’s toboggan track, tends to persist.

Beavers are nothing like as numerous in Northeast Oregon as they were a couple hundred years ago, before trappers decimated the populations to claim the luxurious, and valuable, pelts.

But the industrious rodents are still around, and the Sumpter Valley Dredge State Heritage Area — I prefer to just call it a state park — in Baker County is a fine place to see evidence of their exploits.

Among its attributes, Sumpter is all but certain to have snow throughout winter — and often as not into spring as well.

We stopped at the dredge on Dec. 12 on the way back from a snowshoe hike on a forest road a few miles away.

While I was preoccupied flying our new drone, my wife, Lisa, and our kids, Olivia and Max, went for a short stroll.The park has about 1.5 miles of routes built among the linear piles of stones and gravel — the tailing piles — that the dredge expectorated in its quest for gold.

They found some intriguing marks beside the Powder River, which flows through the tailings.

We speculated that these zig-zagging trails might have been made by a beaver’s tail.

I showed a few photos to Brian Ratliff, district wildlife biologist at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Baker City office, but the photos didn’t have enough detail for him to make a definite identification.

Ratliff told me that beavers generally don’t walk in the zig-zag pattern of the marks Lisa photographed.

Other possible culprits for trails in the snow at the park include, in addition to beavers, their smaller furbearing rodent cousin, the muskrat, as well as river otters. All of these species, none having a great deal of ground clearance, can impress trails into snow as they lumber along.

Otters, of course, are known for their playful slides down snow slopes.

Tracks, slides and trails aren’t the only types of spoor you can see in the dredge park.

You probably won’t have to search long to find streamside trees and brush that have been gnawed by beavers. The animals rely on willows and other deciduous trees for food as well as the raw material for their dams and lodges.

A couple of years ago the park’s beavers, being inveterate dam-builders, inundated a section of trail that’s since been slightly elevated.

The park is also the birthplace of the Powder River.

The spot, marked by a trailside sign, is where two streams, McCully Fork and Cracker Creek, converge to create the Powder.

The Sumpter Valley Dredge State Heritage Area is on the south end of Sumpter, a town of about 210 residents that’s 28 miles southwest of Baker City, via Highway 7.

Although the dredge itself is closed during winter, the park is open and visitors can snowshoe around the frozen pond in which the 1,240-ton, three-story gold-mining behemoth rests, and on the 1.5-mile network of trails. Parking is limited in the area but a small area is plowed near the state park office.