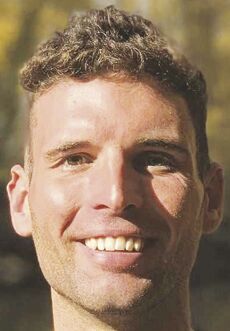

Caught Ovgard: Shooting for the stars in Hawaii

Published 3:00 am Saturday, November 4, 2023

In January of this year, Pepsi rebranded Sierra Mist to Starry. Virtually no one noticed. OK, people noticed, but people didn’t really care.

Trending

Sprite (owned by global soft drink market leader Coca-Cola) and 7-UP (owned by the conglomerate Keurig-Dr. Pepper, a distant third in global soft drink sales) continuously outperformed whatever lemon-lime drink Pepsi (second in the global market) could come up with.

Despite its best efforts, Pepsi couldn’t get one up on its rivals in this particular market — let alone 7-UP — so it pushed “RESET” on a product that had been on the shelves since 1999.

Personally, I respected the move. I’m not a soda drinker, but the industry is a fantastic gauge of the world market since virtually every citizen of every nation consumes soft drinks. Few physical products come in so many varieties and are found in so many places. They come and go, but some (such as Coca-Cola) are more long-lived. Coke has made the Fortune 500 since the list was first conceived in 1955. About 50 other companies can make this claim, but less than a dozen predate Coke’s 1886 origin.

Trending

Dr. Pepper is a year older, hitting shelves in 1885.

Pepsi, a relative latecomer in 1893, is still ancient by corporate standards.

How these companies have adapted and changed is a testament to human resolve.

In today’s world, flexibility is necessary for survival.

The natural world is no different.

Harbor

Hawaii’s Garden Island, Kauai, is known for lush greenery, waterfalls and an ecosystem that has been dealt blow after blow by human habitation. Somehow, Kauai keeps rolling with the punches. From the horde of half a million invasive chickens (moa) that plague the island to peacock grouper (roi) that can kill those who eat their Ciguatera-ridden flesh, humans have really messed up paradise.

Though these invasive species are very visible, other negative human effects are less so.

Effects such as impaired water quality. In Kauai’s few industrial harbors, the aquatic sludge is only visible when water is calm and skies are clear, but the rust-colored sludge mixes into the algae and vegetation and coats the rocks. In harbors with this toxic algae full of fuel, heavy metals and other poisonous particulates, fish and shellfish are spread much more thinly.

Observers will also typically see far lower species diversity in these areas, too, affording only the hardiest species to survive and then dominate an ecological niche instead of several species sharing the space harmoniously.

A clean natural harbor might have a few species of thumb-sized bottom dwellers creeping around the rocks, two or three kinds of morays, several species of schooling filter feeders, a medium-sized, bottom-hugging predator or two, half a dozen reef fishes and a large shark, but these polluted harbors are comparative dead zones.

One small industrial harbor on Kauai’s southeastern coast was a perfect example of this imperfect treatment of the water.

A few snowflake morays peeked out from rocks covered in dead, brownish algae mixed with ship rust and chipped paint. Their heads swayed in the current, trying to snag one of the Hawaiian silversides filling the water column in lilting, shimmering schools under the oil slick on the surface.

A handful of stray blacktail snapper (an invasive species) lurked in shadows under the infrastructure.

On the sludge-covered rocks, darting this way and that, I could see tiny gobies.

Assuming they were frillin gobies of some kind (very common in Hawaii), I ignored them at first. Then, I found a corner of the harbor not swirling with sediment, the light changed and those perfect conditions that allow you to see the true condition of these polluted harbors came to pass.

Dark, gherkin-sized fishes with what appeared to be shimmered blue and purple spots shot out, rested briefly on the sun-illuminated rocks and then darted back into the crevices from which they’d come.

Seizing my chance, I put my pea-sized piece of shrimp into a crevice and quickly caught one of the most beautiful little fishes I’d ever seen, the starry goby, Asterropteryx semipunctata.

The dark background punctuated with deep, iridescent purple-blue and white spots make this fish look like the ceiling of a planetarium.

You can almost hear Neil Degrasse Tyson narrating each individual goby’s life story.

Friends have caught them in Fiji and other islands of the South Pacific, but in waters just as pristine and clear as the bottled water bearing the island’s name — certainly not in polluted harbors too dirty for swimmers.

Still, this little fish had not only persisted here but actually dominated the locality. I caught half a dozen of the beautiful little dudes before realizing there wasn’t much else.

Though Pepsi probably didn’t consult the harbormaster before rebranding its lemon-lime soda, the starry goby proved that day to be a fish of second chances, so Pepsi could not have chosen a better name for its second-chance soda than Starry.

Whether it can catch Sprite or 7-UP remains to be seen, but at least Pepsi shot for the stars.