Out and About: Climbing through the Columbia River Gorge’s geologic history

Published 7:22 am Tuesday, May 27, 2025

Hiking in most of the higher mountains of Northeastern Oregon, with their muddled layers of stone, is akin to tramping through several chapters of a geologic textbook.

The Columbia River Gorge is more like a single sentence.

Or perhaps a couple of paragraphs depending on how precise the definition.

In a general sense, though, the Gorge’s stony history is simple compared with those of the Wallowas, Elkhorns, Greenhorns and Strawberry ranges.

On many trails in those mountains, your boots are apt to land on several types of rock spanning a range of colors, texture and ages.

In the Wallowas, where the strata are especially jumbled, you can over several miles kick gray limestone more than 200 million years old, white granodiorite about 70 million years younger, and dark brown basalt that is a youngster by comparison, having spewed out of the Earth just 16 million years or so ago.

In the Gorge, by contrast, if you stub a toe on a chunk of rock jutting from the trail it’s almost certain to be basalt.

And a particular brand of basalt at that.

The great walls of stone that the Columbia River sliced through on its route to the Pacific, some looming more than 4,000 feet above the river, are almost exclusively part of the formation that geologists call the Columbia River flood basalts.

Rarely has the planet expectorated such volumes of lava as these outpourings from around 16.6 million to 6 million years ago.

And although some of those rocks are now buffeted by breaking waves of saltwater, they are, in a sense, natives of Northeastern Oregon, more than 250 miles from the shore.

The vents from which these fluid lavas issued — the lack of viscosity partially responsible for the vast distances they traveled — are clustered in the northeast corner of Oregon and the southeast corner of Washington.

Some of the basalt stayed close.

Much of the western Wallowas are made of Columbia River basalts, including China Hat and Burger Butte, the prominent peaks above the Catherine Creek drainage southeast of Union.

Flood basalts also are the dominant rocks in the northern Blue Mountains. The tall roadcuts along Interstate 84 between La Grande and Pendleton, including the most dramatic ones on Cabbage Hill, cleave these basalt flows.

But it is with good reason that geologists attached the name Columbia River to these formations. The great river of the West has exposed the monumental scale of the basalts, an upheaval all but beyond our comprehension.

Ellen Morris Bishop, the renowned Oregon geologist and author, offers a piquant example to illustrate the scope of the flood basalts in her fine book, “In Search of Ancient Oregon,” which I believe deserves a place in the bookshelf of anyone passionate about our state. The Grande Ronde Basalt, which makes up about 85% of the volume of the Columbia River Basalt Group, produced an estimated 35,000 cubic miles of lava. That’s enough, Bishop writes, to build a 7-foot-thick, 100-foot-wide basalt road to the moon.

Pretty much any of the dozens of hiking trails in the Gorge offers an introduction to these copious basalts.

But few are as accessible, or lead to a more dramatic vista, than the path to Mitchell Point a few miles west of Hood River.

And then there’s the new tunnel.

More about that later.

Mitchell Point

If you’ve driven I-84 between Hood River and Portland, at least during the daylight and not during a blizzard, you’ve seen Mitchell Point.

Even if you didn’t know its name.

The point is the prominent pinnacle just south of the freeway near milepost 58.

Mitchell Point, which rises more than 1,100 feet above the river, and its lower satellite summit, known as Mitchell Spur, are both made of Columbia River basalt.

But not quite the same basalt, according to geologists.

The spur, and the cliffs near the Mitchell Point Trailhead parking lot (accessible only from the eastbound freeway, exit 58), are Grande Ronde Basalt, which erupted from around 16.5 million to 15.6 million years ago.

Mitchell Point itself, though, is a trifle younger (by geologic standards, anyway). It was formed from the Wanapum Basalt, which dates to around 14 .5 million years ago. These lavas spewed from vents between Pendleton and Hanford, Washington.

The geologic picture on Mitchell Point is slightly more complicated, though, as the two basalt flows are separated by outcrops of the Troutdale Formation, sedimentary rocks deposited by an ancestral Columbia River.

The new tunnel

Access to the trailhead was closed for more than a year while the Oregon Department of Transportation built a new tunnel, open to hikers and bicycles, as part of a 1.5-mile segment of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail, a recreational corridor that retraces the historic 73-mile Historic Columbia Highway between Portland and The Dalles.

The tunnel was dedicated in November 2024, and the trailhead parking lot opened earlier this spring.

The Mitchell Point Tunnel mimics an historic tunnel, of the same name, that was blasted from the basalt cliffs when the original Columbia River Highway, Oregon’s first major highway, was built in 1915. The tunnel was famous for its arched windows facing west toward the river, a feature the new tunnel replicates.

The state closed the tunnel in 1953 due to safety concerns. In 1966, crews destroyed the tunnel as part of a project to widen Interstate 84.

The tunnel is a short stroll from the parking lot.

Hiking to the top

The trail to Mitchell Point’s summit is not a stroll.

Although the trail is well-maintained it’s also steep, climbing about 1,200 feet in just 1.3 miles.

From the south side of the parking lot, walk uphill on the paved path and stay straight where the pavement ends.

The grade is moderate for the first quarter mile or so, the climb eased by a few switchbacks.

But this gentle introduction is brief.

The trail alternates between shady sections through trees — a mixture of bigleaf maples and Douglas-firs — and exposed slopes where the route goes through rockslides. The latter can be a bit treacherous, as the combination of scattered rocks and the steep grade calls for cautious hiking.

Just before the summit, the trail winds through the right-of-way for a power transmission line. At a junction the trail makes a 90-degree turn to the left (north) and follows a fin of basalt to the top.

This is no rock climb, to be sure.

But the ridge is narrow enough, and the dropoff to the west sheer enough, to induce a slight tremor in some hikers’ legs.

(Mine, for instance.)

Although the spine of Mitchell Point extends to the north, you won’t get any better views by venturing onto the dangerous ground beyond where the trail peters out.

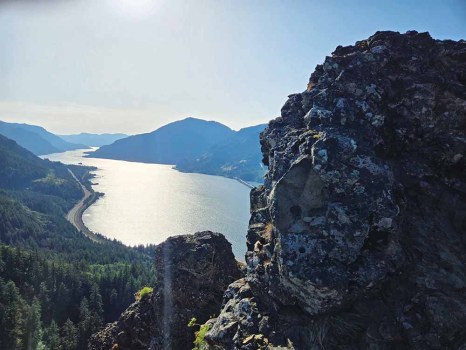

As for those views, the vista is about as close as you can get to an aerial tour of the gorge without climbing into an aircraft.

Traffic teeming on the freeway, about 1,100 below, seems insignificant, the hum of the tires barely audible (and perhaps not at all if the wind is blowing, as it most generally is — the gorge is a sort of giant funnel).

I made the hike on May 24, the Saturday of Memorial Day, and it was a rare calm evening. I saw only a few windsurfers — and one sailboat — plying the Columbia.

On a more typically blustery day I suspect the river traffic would be commensurately thicker, the bright-colored sails gliding hither and yon.

The view to the south isn’t quite so stirring, mainly the densely forested slopes that serve as a transition from the gorge to the Cascade Mountains. The highest point to the southwest is Mount Defiance, the nearly 5,000-foot summit named because it holds its snow longer than any nearby mountains, in defiance of summer.

Mitchell Point is known for its wildflowers as well as its views. The peak of the spring show has passed, though. Poison oak, however, remains, and is particularly prevalent in the upper one-third of the trail, including through the power line right-of-way.

Jayson Jacoby is the editor of the Baker City Herald. Contact him at 541-518-2088 or jayson.jacoby @bakercityherald.com.