Baker City woman backing bill that would help herself and other disabled workers

Published 8:10 am Monday, April 28, 2025

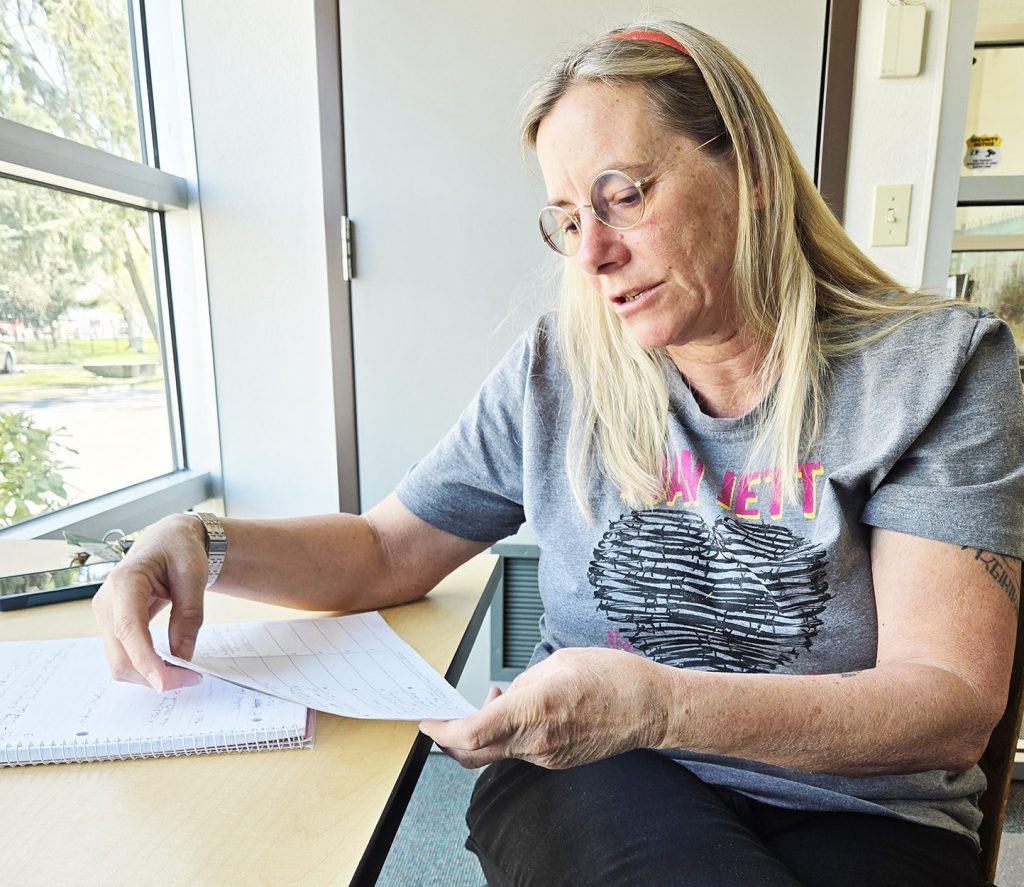

- Chris White of Baker City supports a bill in the Oregon Legislature that proponents say would make it easier for White and other disabled workers to stay enrolled in a state program that includes health insurance. (Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald)

Chris White is disabled after undergoing a series of surgeries over the past 15 years that removed most of her large intestine.

But White, 59, who has lived in Baker City since 1989, still works.

This is possible, she said, in part due to a state program that allows her to keep her Medicaid health insurance benefits by paying a $100 monthly fee.

But White said the Employed Persons with Disability program, overseen by the Oregon Department of Human Services for more than 20 years, has limits on participants’ income and savings accounts that she believes discourages, rather than encourages, some disabled Oregonians to work and to amass savings to cover unexpected expenses.

“I worked three jobs for 30 years,” White said. “I love working. I love being out helping people.”

White said her ability to work long hours was seriously curbed, though, after her first surgery in 2010.

She started receiving Social Security disability payments in 2017 and enrolled in the state program for disabled workers in 2019. She worked as a waitress at the Baker Truck Corral for seven years, but recently moved to the Inland Cafe. She works six hours per week as a waitress.

White said that although the loss of most of her large intestine makes it difficult for her to eat and to absorb nutrients, she could potentially work more hours.

But if she added more than three hours of work per week, she said she has been told by state workers that she would reach the income limit for the state program and risk losing the medical coverage she depends on and can’t otherwise afford.

The additional income from increasing her weekly hours wouldn’t be nearly enough to make up the difference if she were removed from the state program, she said.

“I’m stuck in this little bubble,” White said.

Her Social Security disability income is $1,123 per month. She makes about $275 per month from her job.

(According to a letter to the legislature from Jane-ellen Weidanz, deputy director of policy for the Department of Human Services’ Office of Aging and People with Disabilities, “unearned income,” such as Social Security payments, is not counted toward income limits for people in the disabled worker program.)

White supports a bill in the Oregon Legislature, Senate Bill 20, that would get rid of the limits on both income and on assets for participants in the disabled worker program. The bill, if it becomes law, would require the state to remove the limits by July 1, 2027.

About 2,700 Oregonians are enrolled in the program, according to a state estimate.

To remain eligible, White and others enrolled in the program can’t earn more than 250% of the federal poverty level. They also can’t have assets of more than $5,000, including bank accounts, stocks and bonds, and vehicles. If a participant owns a home, its value isn’t counted toward the asset limit.

The federal government, which oversees Medicaid, allows each state to set income limits or to waive limits altogether.

The Senate Committee on Human Services voted 3-2 on April 7 to send SB 20 to the Ways and Means Committee, which has yet to set a hearing.

A total of 87 people testified in favor, or sent comments in favor, of the legislation for a hearing on Feb. 18.

Similar bills failed to gain traction in the legislature in 2021 and 2023.

State officials estimate that if SB 20 becomes law, about 320 more people would enroll in the Employed Persons with Disabilities program. That would cost the state an estimated $7 million, according to the fiscal impact report for the bill.

The Oregon Disability Health and Employment Equity Coalition is lobbying for SB 20.

The coalition contends that the current program, with its income and asset limits, creates a “tough choice” for disabled workers.

Andrew Caruana, legislative advocacy coordinator for the Disability Health and Employment Equity Coalition, wrote a letter to the legislature supporting SB 20.

Caruana wrote that the disability worker program has not fulfilled its purpose.

“What was initially envisioned as a way to prioritize fiscal responsibility has resulted in disabled Oregonians being forced to decline raises, remain under-employed, kept us impoverished, and reliant on more public assistance, and, in the worst of cases, forced us to choose between our jobs and access to life-saving medical assistance,” Caruana wrote.

Weidanz, the official from the department of human services who wrote the letter to the legislature, wrote that although the agency is neutral on SB 20, the current income and asset limits “force individuals to choose between work and critical benefits.”

Removing those limits, as proposed in SB 20, would allow disabled workers such as White to “earn and save more without worrying about losing medical coverage, or any long-term services and supports if they qualify for them.”

Other challenges

White said another factor that affects her is the annual cost-of-living increase in Social Security disability payments.

Although those payments don’t count toward the income limit for the disabled worker program, White said Social Security income does apply to other aid programs, such as food stamps.

Cost-of-living increases, although generally 2% or less annually, can push a worker’s income closer to the limit for some programs, she said.

Cost-of-living boosts can also increase the monthly payment that White and other disabled workers pay to stay enrolled in the state program.

The fee, which is based on income, is either zero, $50, $100 or $150, the latter being the maximum, White said.

Oregon’s minimum wage, which increases yearly by statute through 2026, also plays a role.

Through June 30, 2025, the minimum wage in nonurban counties, including Baker, is $13.70 per hour. That list includes 18 of Oregon’s 36 counties, mostly east of the Cascades.

The minimum wage for most of the rest of the state is $14.70. The minimum for the Portland metro area is $15.95.

Starting July 1, 2025, the minimum wage increases to $14.05 for nonurban counties, to $15.05 for most of the rest of the state, and to $16.30 for the Portland metro area.

Although mandated rises in the minimum wage increase White’s income, she said the limit for the state disabled worker program hasn’t changed for several years.