EDITORIAL: Some records don’t tell the whole story

Published 3:18 pm Sunday, May 26, 2024

- Baker's Jaron Long won the 800-meter race at the Ray Uriarte Invite meet on May 3, 2024, at Baker High School.

Rules that are clearly written are in general preferable to ones laden with ambiguity. Clarity eliminates, largely if not wholly, the potential complications of interpretation and subjectivity.

Trending

But what about a rule that, because it is so straightforward, fails to acknowledge the nuances that sometimes distinguish a true transgression from an innocent gesture?

Consider a rule that most of us likely didn’t know existed.

It is Section 11, Article 2 of the National Federation of High Schools Sports Association’s track and field rules. Section 11 deals with infractions in relay races — team events in which each member runs the same distance, handing off a baton to each teammate in turn. Relays often are among the more exciting events during track and field meets, since they pit teams rather than individuals against each other.

Trending

Article 2 reads, in full: “The baton shall not be thrown following the finishing of any relay.”

The penalty for violating the rule is similarly succinct: “Disqualification of the relay team from the event.”

The rule gained sudden prominence during the Class 4A state track meet May 18 at Eugene’s Hayward Field.

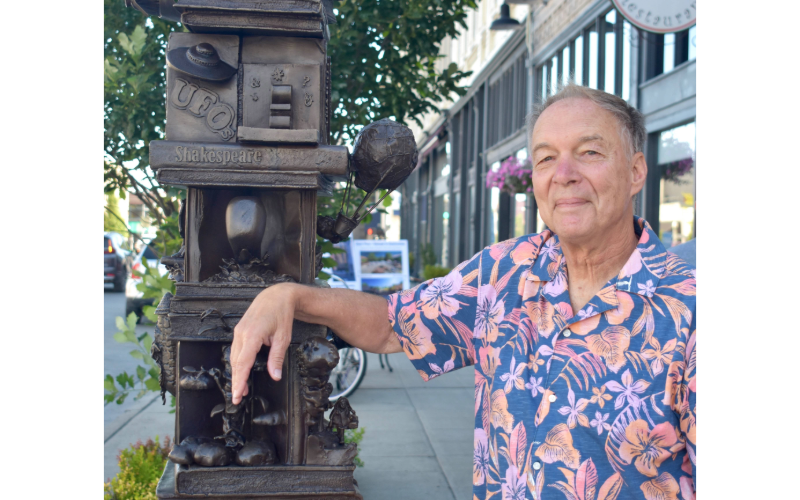

Baker’s 4×400-meter relay team of Malaki Myer, Rasean Jones, Giacomo Rigueiro and Jaron Long was one of the top contenders, having broken the 25-year-old BHS record a month earlier.

Long, running the last (or anchor) leg, crossed the finish line slightly more than two seconds ahead of Bodey Lutes of Marshfield.

Baker’s time not only broke the quartet’s own school record, but it was faster than any Class 4A team had run at the state meet.

But as Long was slowing down, he threw the baton to the track in front of him.

It was, he said later, an almost unconscious reaction to the joy he felt after he and his teammates had fulfilled the goal they had strived for.

Long didn’t know about Article 2 of Section 11.

But he concedes he broke it.

Baker was disqualified, deprived of their medals and the meet record.

Based on the rule, this is the appropriate outcome — indeed, given the clarity of the rule, it is the only reasonable outcome.

But is the rule itself reasonable? Which is to say, is it fair?

That there should be a rule at all, regarding how runners handle the baton even after finishing a race, is understandable. Runners shouldn’t be heaving metal batons. There are other runners, event officials and spectators within range.

Nor is it unreasonable to have a rule which punishes athletes who taunt opponents or otherwise act obnoxiously in the afterglow of victory.

But Long said that was in no way his intention.

And based on a video of the relay finish and immediate aftermath, it seems quite clear that his decision to toss the baton was a spontaneous, undramatic gesture little different from jabbing at the sky with a clenched first or yelling in triumph, as athletes frequently do after winning.

He wasn’t, as Long himself put it, “showboating.”

Long, of course, will almost certainly keep his grip on the baton after every relay in which he competes from here on.

And likely any other runner who learns of Long’s and his teammates’ fate will be equally protective of that metal cylinder.

So perhaps the rule needn’t be changed now that its repercussions have been so amply demonstrated.

Still and all, it is reasonable to wonder whether the rule, even at the expense of adding words and, inevitably, subjectivity, might benefit from language that protects harmless gestures from obnoxious or even dangerous ones.

In the end, Long, Jones, Myer and Rigueiro know — as everyone knows who cares about the matter — that they won the race and set the record. They will have to trust that history, if not the Oregon School Activities Association record book — will tell their story properly.