Column: COVID-19 brought unforeseeable challenges for hospital systems

Published 4:00 am Friday, June 19, 2020

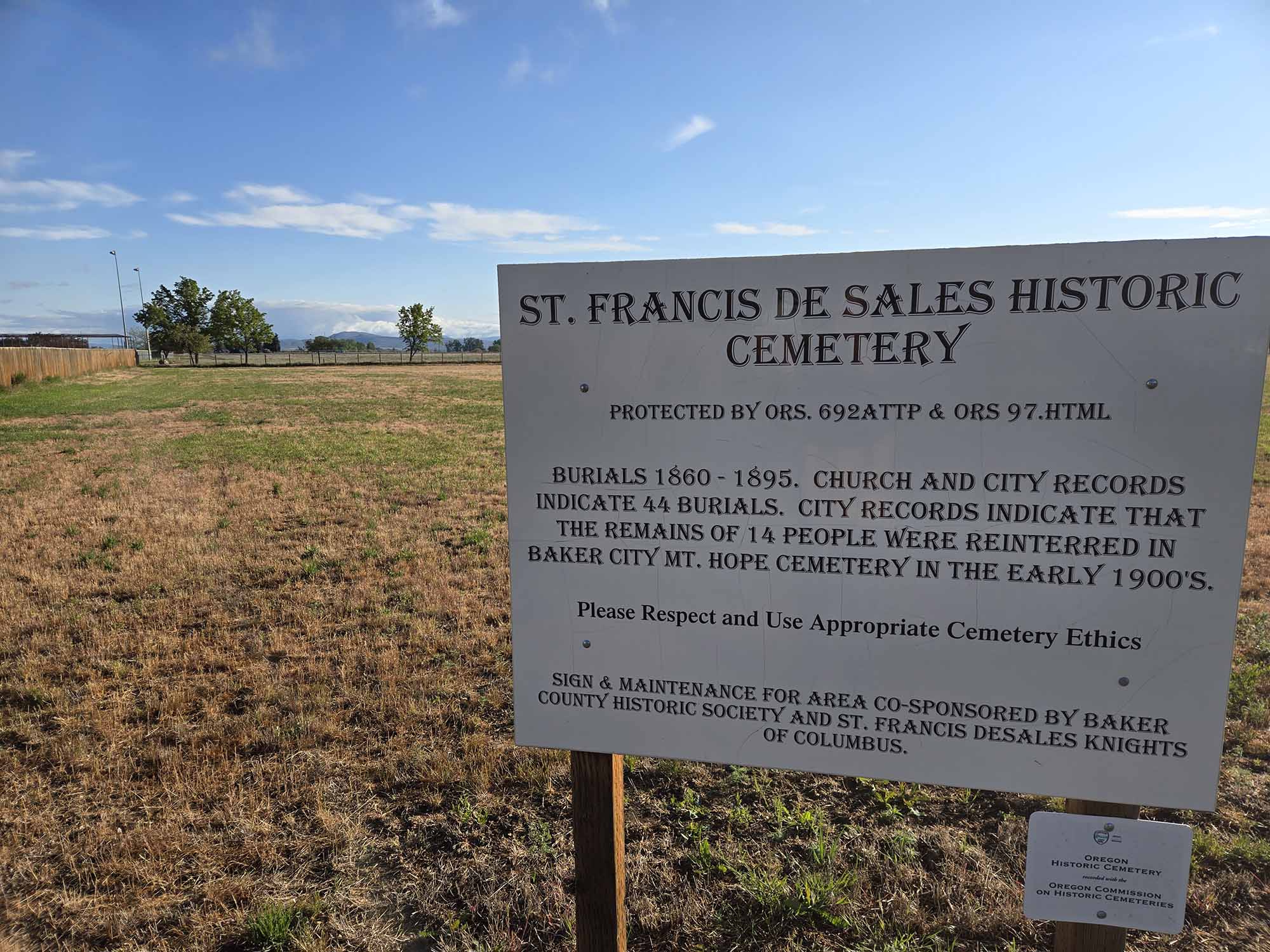

- A tent goes up outside the emergency room entrance at St. Charles Redmond on Friday, March 13, 2020 in preparation to triage incoming patients with COVID-19 symptoms.

When Deschutes County’s first case of COVID-19 was announced at a press conference March 11, Dr. Jeff Absalon stood before a room of reporters and elected officials and assured the community that St. Charles Health System was ready.

Trending

The organization had been expecting this moment for many weeks and preparing for just as long.

“As a health system, we see patients with infectious diseases every day,” said Absalon, chief physician executive and one of two incident commanders for the health system’s COVID-19 response. “This is our job. This is what we are prepared to do.”

As the weeks unfolded, it became clear that St. Charles — and indeed hospital systems around the country — would be tested in ways it had never been before. In 2009, many health care leaders had worked through the public health and operational challenges of the H1N1 virus, which caused the first global flu pandemic in 40 years. But the sheer speed and scale of the COVID-19 crisis coupled with the economic devastation it wrought made the experience unlike any other.

Trending

“There’s no playbook for this,” said St. Charles President and CEO Joe Sluka, “so there’s a lot of not knowing what comes next. In this sort of situation, you have to rely on the excellent leadership you have in the organization and the expert caregivers who feel comfortable working through a crisis.”

With its pandemic plan and predictive models guiding its work, St. Charles’ Incident Command — the leadership team the health system convenes to manage emergencies — prepared to meet the needs of a huge influx of sick patients. That meant making plans to expand to 610 beds (when normally the health system has 287) as well as ensuring there was enough personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators to safely care for patients.

“It took a lot of skill and effort on a lot of peoples’ part,” Sluka said. “We even adjusted peoples’ work, asking our nurses, for instance, to be reassigned to new and really important roles in our labor pool. Because of that, we were able to double our bed capacity and change our workflow in very short order.”

To prevent the spread of the virus and help create bed capacity, St. Charles swiftly put into place visitor restrictions and halted all surgeries except those considered urgent. In the early weeks of its response, the health system also moved to conserve its rapidly dwindling supply of nasopharyngeal swabs by instituting COVID-19 testing criteria that were even more stringent than those recommended by the CDC.

The swabs, it turned out, were just the beginning of the health system’s challenges trying to secure the medical supplies it needed. Significant disruptions in the global supply chain made it at times impossible to predict if and when mission-critical safety gear like N95 masks, isolation gowns, nitrile gloves and hand sanitizer would show up. It could arrive in weeks. Or months. No one knew.

The shortage of supplies grew so dire that by March 19 the health system put out an unprecedented and urgent call for PPE donations. Schools, dentist offices, auto shops and many other businesses and individuals jumped in to help, dropping off loads of PPE at collection sites at local elementary schools. Still others contributed to the effort by manufacturing plastic face shields and sewing cloth masks. It was a remarkable outpouring of support that made it possible for frontline caregivers at St. Charles hospitals and clinics to safely do their jobs.

By April 5, St. Charles’ first COVID-19 surge peaked at 14 patients, many of whom spent some time in the Intensive Care Unit.

But St. Charles continues to keep a watchful eye on the number of positive cases in the region, the number of patients who are hospitalized and its supply of PPE (even now the health system continues to operate in conservation mode due to continuing shortages). Until there is a vaccine and, ultimately, herd immunity, St. Charles will have to be prepared for the possibility of more patient surges.

COVID-19 has been disruptive — from the way the health system triages patients in its emergency departments to how its physicians run appointments to how it manages its finances, it all looks different now. But ask Sluka and indeed others in the organization and they’ll tell you much of the change is for the better.

“Even though we stand 6 feet apart, I think this event will ultimately bring Central Oregon closer together,” he said. “I am proud of the innovation and collaboration of this organization and our community. It has been inspiring for me.”