Our Mountains as Measuring Sticks

Published 3:14 pm Friday, May 26, 2017

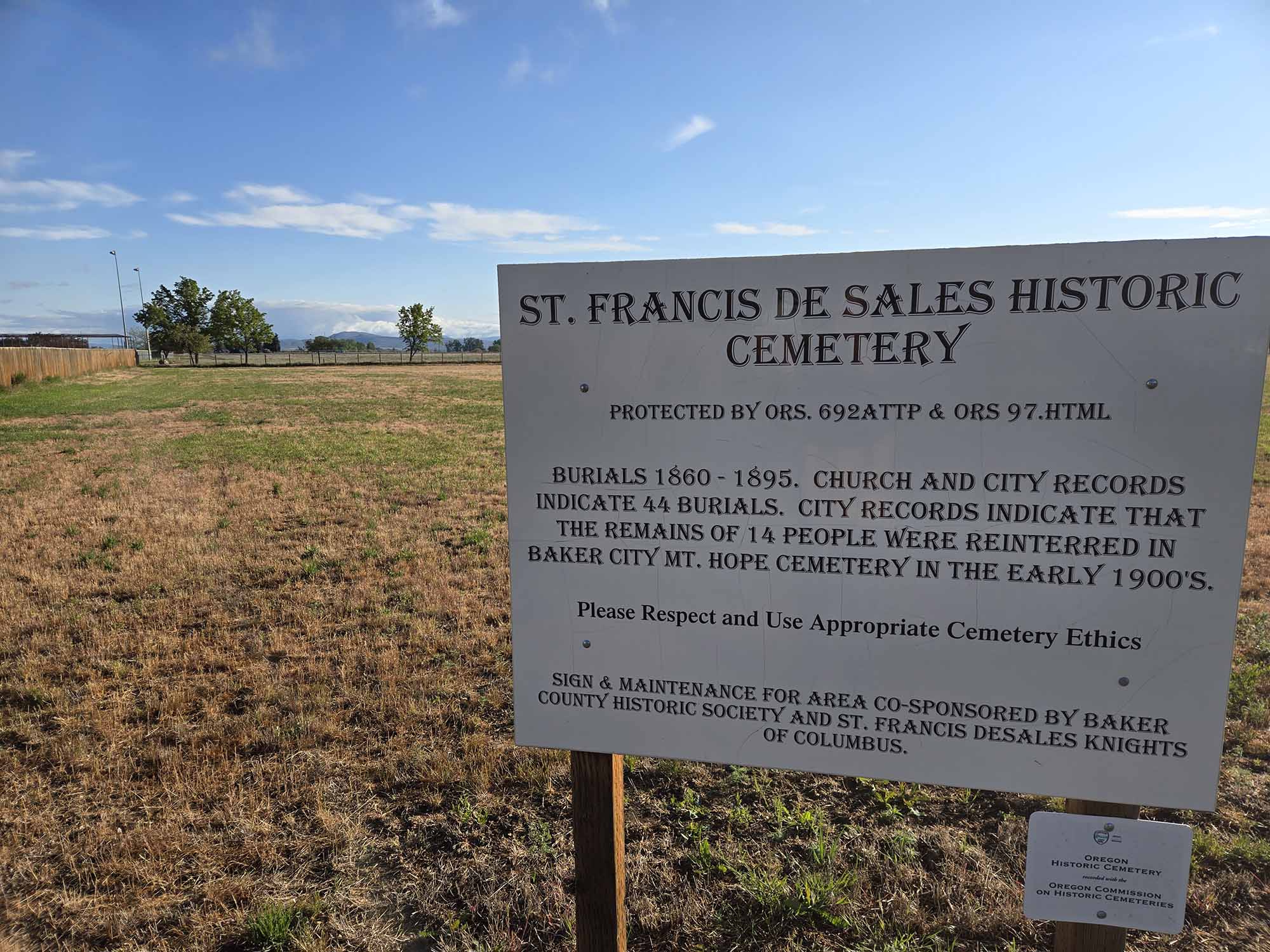

- Photo by Ellen Morris BishopThe northern slopes of the Wallowa Mountains loom over the Wallowa Valley.

We expect much from our mountains, we who live sometimes literally in their shadows, and in the main our mountains deliver.

Trending

They fulfill our most basic need by pilfering rain and snow from passing clouds and then doling out the water to slake our thirsts and nourish our crops and give our kids something to splash in.

(Although kids seem to be satisfied with the bathroom floor.)

They help us keep our legs and our lungs in fine fettle by beckoning us to climb their steep slopes.

Trending

And mountains satisfy our peculiarly human longing for natural beauty by flaunting their precipices and fields of snow.

This last attribute, it seems to me, gives mountains their personality, at least to the extent that word can be applied to piles of stone and dirt.

We are fortunate in Northeastern Oregon to have such grand mountains close by.

So close that we see our mountains in all their myriad guises — and how different these can be.

Mount Emily’s shape might as well be eternal from our puny perspective of time, its basaltic lantern jaw forever jutting over the Grande Ronde Valley.

But the peak, on the clear dawn after a January blizzard, scarcely resembles what we see at, say, dusk in July or afternoon in late October when the tamaracks are blazing.

The same applies to all the classic vistas of our region — the Elkhorns from the Baker and Sumpter valleys, the Wallowas from Enterprise and Joseph to the north, and from Richland and Halfway to the south, and many others besides.

These seasonal differences in appearance are not so great with glaciated mountains such as Hood and the Three Sisters and several other Cascade volcanoes that from certain angles glisten white clear through summer.

I rather like that the Wallowas and parts of the Blues, though their current shapes were sculpted by ice, in our more temperate modern climate shed all but tiny remnants of each winter’s accumulation of snow.

(The region’s last glacier, the Benson, on the north slopes of Eagle Cap, was relegated to the status of stagnant snowfield rather than moving river of ice somewhere around the Second World War.)

The absence of glaciers means we can look at our mountains and gauge how far along spring has advanced.

The measuring stick, as it were, differs not only depending on the mountain, but, in the case of each mountain, with our vantage point.

To cite an obvious example, south- and west-facing slopes, owing to their greater exposure to the sun, lose their snow much earlier than north and east slopes do.

So it is that the Wallowas, as seen from La Grande, show little or no snow even while the peaks above Joseph are still largely white.

I live in Baker City so it’s the Elkhorns, scarcely 10 miles to the west, that I know best.

My favorite bellwether in the Elkhorns is Marble Creek Pass. It’s the last gap in the sedimentary wall of the mountains before the range plunges south to the valley of the upper Powder River.

But it’s not the pass itself that I peruse to assess spring’s advance.

Rather it’s the cornices that build each winter above the road just below the pass.

The Elkhorns would hardly have been better positioned to encourage cornices if they had been designed by an architect who intended that particular result.

The spine of Elkhorn Ridge runs slightly west of north, which puts it generally perpendicular to the prevailing direction of winter winds.

The result is that the great gales which accompany snowstorms pause briefly when they crest the ridge, allowing much of the snow to settle on the top and just a short way to the leeward.

The resulting cornices overhang, rather like ocean waves that were frozen just at the instant they began to break on a reef.

The same thing, albeit at a much smaller scale, can happen on the roof of your house — or even the roof of your car — after a heavy fall of powdery snow accompanied by wind.

(Hardly an uncommon set of circumstances in La Grande or Imbler or North Powder, among other local spots.)

The Marble Creek Pass cornices are tall enough that on sunny days in winter and early spring they cast shadows that are plainly visible even from Baker City.

By Memorial Day, at least in most years, much of the ground around the pass is bare of snow, leaving the cornices — or, sometimes, a single cornice — as a conspicuous white slash across the drab brown background.

But the distance, as distance does, misleads the eye. What looks from Baker City to be a mere scrap of snow, something you probably could hop over to keep your boots dry, in fact is a cornice remnant that’s 4 feet deep and will block rigs from crossing the pass for a couple more weeks.

This is a minor bit of knowledge to acquire, I concede, and hardly the sort of thing I might employ in a bet over who buys a round of beers.

But it’s also the sort of detail that binds us to our mountains, that compels us to look at them and that makes the looking seem worthwhile.

A goodly number of us around here, I suspect, have their own version of Marble Creek Pass, some ridge or knob in the Wallowas, some cleft in the slopes of Mount Emily or Mount Harris or Mount Fanny that they consult each spring, as a farmer might examine a shovelful of dirt to decide when to sow the year’s crop.