In Oregon’s biggest wild area, even the small parts sprawl

Published 3:14 pm Friday, May 26, 2017

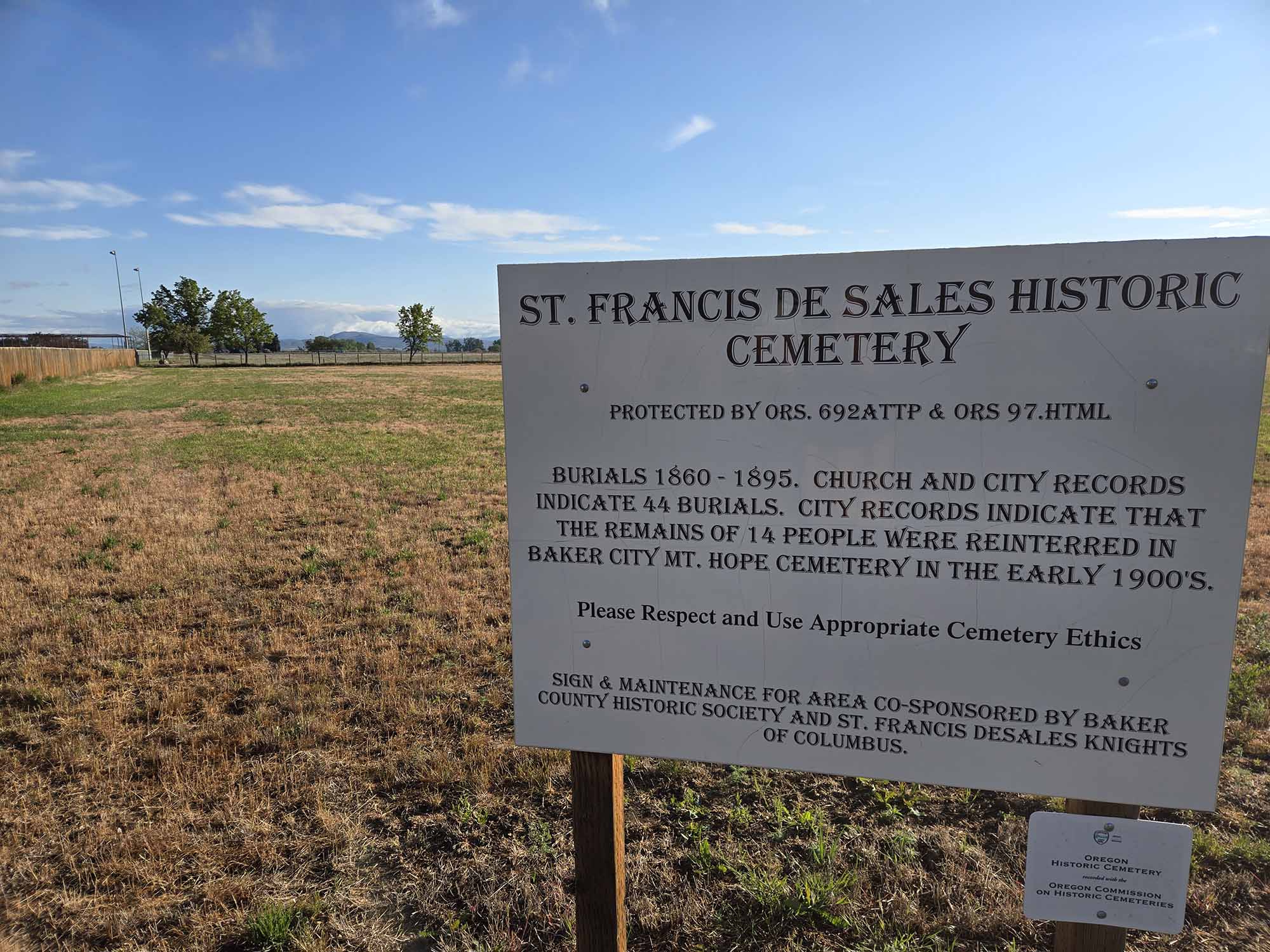

- Stuart Hills photoEagle Lake is in a stark glacial basin. A dam built around 1919 increased the amount of water the natural lake can hold for irrigation use downstream in Baker County.

The Eagle Cap Wilderness is so big that even its small corners sprawl magnificently.

Trending

The most detailed map, hamstrung by its mere two dimensions, utterly fails to convey the scale of the Eagle Cap.

Conventional measurements such as square miles and acres simply will not do here.

You could point out, and you would be right, that the Eagle Cap, at 365,000 acres, is Oregon’s largest wilderness.

Trending

But a square mile in the Eagle Cap is not like a square mile in most places.

An Eagle Cap square mile might include the summit of a 9,000-foot peak and a lake more than a thousand feet below and a couple of streams in between.

To put it another way, a square mile in the Eagle Cap can have quite a lot more country crammed into it than that modest area, as depicted on a paper map with perfectly straight lines, suggests.

I was reminded of this trait during a two-day, 21-mile backpacking trip in the Eagle Cap last weekend.

So were my feet.

The section that my friend Stuart Hills and I visited accounts for maybe 5 percent of the Eagle Cap’s acreage.

Yet I was struck, as I always am when I tramp about this wilderness, by its vastness.

Except for a brief venture over a pass and into the upper Trail Creek basin, we stayed within the main Eagle Creek drainage.

Although this is one of the major streams draining from the Eagle Cap, on a map it covers what looks to be an insignificant portion of the wilderness.

But if you wanted to make even a moderately thorough inspection of Eagle Creek, to have a cursory look into each of its tributary basins and to sample its ridges and peaks, you’d need to devote a couple weeks of hard hiking, most of it cross country.

And in my case a new pair of boots and the better part of a bottle of ibuprofen.

Stuart and I confined our travels to designated trails but we didn’t come away feeling deprived of scenery.

Our route, which starts and ends at the Main Eagle trailhead, is one I followed once before, about 15 years ago.

We had only one night to spare so Cached Lake, near the midpoint of the trip, was the obvious choice for our campsite.

But the route is ideal for a two-night, three-day itinerary as well.

With that option you could camp one night at Cached Lake and the other at Arrow Lake which, rare among lakes in the Eagle Cap, lies near the top of a divide rather than in a basin.

Allotting three days rather than two also means you don’t have to climb two passes in one day.

We hiked the loop clockwise but of course you can do the opposite.

Either way you start by following the Main Eagle trail for about three miles to the junction with Bench Canyon trail.

This is a pleasant start to a backpacking trip, as the path is never steep and in general it stays companionably close to Eagle Creek, a fetching mountain stream that boasts the crystalline pools and frothy rapids that distinguish such waterways.

The trail crosses the creek three times in this section.

The first, about half a mile from the trailhead, is by way of a solid bridge with a fine view of a waterfall just upstream.

The latter two crossings require a bit more dexterity.

The middle crossing is, quite literally, a bridge to nowhere. The wooden structure that once spanned Eagle Creek has collapsed, so you’ll either have to wade across just downstream from the bridge — a pair of flipflops or old sneakers is a handy, and not terribly heavy, way to spare your hiking boots and socks from a dunking — or tiptoe on a trio of logs 50 feet or so upstream.

The next stream in your path is not Eagle Creek but one of its main tributaries, Copper Creek. There’s no bridge here, either, but the creek’s flow, by August, is sufficiently scanty, and the rocks large and plentiful enough, that you needn’t be particularly nimble on your feet to get to the other side with dry boots.

(I’m far from nimble, and I made it with nary a splash.)

Just before the Bench Canyon trail junction, Eagle Creek, probably some spring when it was especially flush with snowmelt, carved a sinuous series of channels, creating something like the delta at a river’s mouth.

But this ford is similar to the one at Copper Creek, and is not a major obstacle.

The Bench Canyon trail junction has the only signpost we saw in which the sign was still attached to the post.

Two signs, in fact, the most important of which bears a simple message: “Trail Not Maintained.”

This is accurate enough, in that no one from the U.S. Forest Service, the agency that manages the Eagle Cap, seems to have wielded a shovel or a crosscut saw on the Bench Canyon trail for years if not decades.

But in my view the trail’s main deficiency is not its lack of basic maintenance but rather a more fundamental flaw — its design.

Bench Canyon eschews the trademark of most Eagle Cap trails — the grade-easing switchback — for a straightforward assault on the canyon’s steep wall.

In its nearly 2,000-foot climb to the pass at Arrow Lake, the trail has fewer than 10 switchbacks. A typical Eagle Cap trail would incorporate perhaps four times as many for a similar elevation gain.

The Bench Canyon trail is comparatively short as a result — just 2.3 miles from Main Eagle trail to Arrow Lake.

But just as a square mile in the Eagle Cap is no ordinary square mile, those 2.3 miles of trail bear little resemblance to, say, a stroll of the same distance on a sidewalk.

Arrow Lake makes a nice reward for your toil, though.

It’s a smaller lake than most in the Wallowas, covering just a few acres, but the setting is spectacular.

A granitic peak looms over the lake’s western shore, but the east side seems almost poised on a precipice. From the pass, just a couple hundred feet from the lake, the view extends west to the peaks above Echo and Traverse lakes, and down Trail Creek to the dense forests of the Minam River Canyon, longest in the Eagle Cap.

The scenic cherry on this sundae — although it’s not bright red — is the snow-white marble tip of the Matterhorn, about 10 miles to the northeast.

From the pass the trail plummets, again with a distinct aversion to switchbacks, for half a mile or so to a junction (post and granite cairn, but no sign) with the Trail Creek trail.

Turn right here (again, this is based on hiking clockwise) and climb 800 feet, albeit at much gentler grade thanks to frequent switchbacks, to another pass.

This pass has no name, which seems to me curious as its views are as spectacular as many named passes in the Eagle Cap. The prominent reddish-brown mountains to the southeast are Krag Peak and Red Mountain, the latter being the highest point in Baker County at 9,555 feet.

The trail descends, still at a knee-friendly grade, for about two miles to Cached Lake. The best campsites are on the lake’s eastern shore. These feature views of the nearly sheer cliff above the lake’s western shore, and, to the north, of Needlepoint Mountain, at 9,018 feet the tallest (and aptly named) peak in the Eagle Creek drainage.

From Cached Lake the remainder of the loop is downhill with one exception — the side trip to Eagle Lake.

I strongly recommend this detour.

It’s short — two miles total — the elevation gain is a moderate 600 feet, and the grade is reasonable.

But the real pity would be to hike all these miles and miss seeing one of the prettiest lakes in a wilderness area that’s hardly deficient in that category.

Also, you can stash your packs at the junction and enjoy hiking a couple miles without straps clamping, talon-like, on your shoulders.

Eagle Lake, like several other lakes in the southern half of the Eagle Cap, is a natural lake that’s larger than it used to be since farmers built dams across the lakes’ outlets to store more water for summer irrigation.

Eagle Lake’s dam, made of granite boulders that are in great abundance around the lake, was built around 1919, according to records from the Oregon Water Resources Department.

The setting is much more stark than at many lakes in the Eagle Cap, with just a scattering of stunted whitebark pines. The east shoulder of Needlepoint rises almost vertically from the lakeshore to the summit.

The water is that eerie iridescent blue peculiar to alpine lakes, the white granitic bottom clear more than 30 feet below the surface.

The rest of the hike is anticlimactic by comparison.

But it’s a nice walk, as the trail passes a large meadow along Eagle Creek and bisects the path of at least two avalanches that toppled dozens of trees many years ago.

If You Go…

TRAILHEAD

• The Main Eagle trailhead is at the end of Forest Road 7755, near the site of the former Boulder Park Resort. Two main roads lead to Road 7755. The most convenient if you’re coming from La Grande or Wallowa County is Road 77, which starts at Catherine Creek Summit on Highway 203. The shortest route if you’re coming from Baker City or points south is Road 67, which starts at Medical Springs, also on Highway 203.

• If you park at the trailhead you’ll need to pay a $5 fee.

• Fill out a free wilderness permit before you start hiking

WILDERNESS REGULATIONS

• It’s illegal to light a fire or to camp within 100 feet of lakes in the Eagle Cap Wilderness, including Cached and Arrow lakes. Fires are banned within one-quarter mile of Eagle Lake.