FALL

Published 12:00 am Friday, September 23, 2005

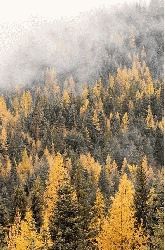

- The Blue Mountains conceal tamaracks until late fall when trees turn orange and shed their needles. (Baker City Herald/S. John Collins).

By JAYSON JACOBY

Of the Baker City Herald

Every fall the camera carriers flock to New England, and there they practically dislocate their shutter fingers photographing a bunch of red and yellow and orange leaves.

Northeastern Oregon has plenty of leaves, too, and they turn the very same colors.

But we’ve also got a lot of trees with needles that act like leaves, a curiosity that adds a touch of intrigue, and a dollop of beauty, to autumn.

Tree experts call them western larches, but around here people are more likely to know what you mean if you say tamarack.

Technically the tamarack is a conifer, which means it produces cones that bear its seeds.

But unlike ponderosa pines and Douglas-firs and all the other local conifers, which horde their needles year-round and so stay green through both blizzard and blistering sun, tamaracks get a bit confused come October.

Their needles, which cluster in soft, fuzzy bundles of 15 to 30 at the end of each twig, first turn slightly pale, like a child who has a stomachache.

As October progresses the pale green fades to a light yellow which by month’s end, as if to celebrate Halloween, blossoms into a bright and quite conspicuous orange.

By Thanksgiving most tamarack needles have fallen to the forest floor, like colorful confetti.

Now to give New England its due, tamaracks grow there, too (although in Maine’s colorful vernacular the trees are known as “hackmatacks”).

But who wants to travel 3,000 miles to the Granite state (New Hampshire) when you can drive to Granite, Ore., which is just 45 paved miles from Baker City?

The fuel savings alone ought to pay for a decent digital camera.

Following is a pair of one-day driving tours, each starting and ending in Baker City, that showcases some of this area’s more colorful autumn performances.

The Tamarack Trail

DESTINATION: Elkhorn Mountains, via a pair of scenic byways: Elkhorn Drive and Blue Mountain

DISTANCE: About 115 miles round-trip

WHEN TO GO: Mid-October to mid-November (snow is possible along this route, however, and between Granite and Baker Valley there are no snowplows, so if the weather turns wintry either bring chains or pick a lower-elevation destination)

PRIMARY COLOR(S): Yellow (aspen and cottonwoods) and orange (tamaracks)

You can go most anyplace in the Elkhorn Mountains and see tamaracks, but this route garnishes their orange entree with appetizers of alpine lakes, the second-highest paved road in Oregon, and groves of two other trees renowned for their fall colors: the quaking aspen and the cottonwood.

Start by driving south of Baker City on Ore. Highway 7, following signs to Sumpter.

This is the Elkhorn Drive Scenic Byway, and it follows the Powder River upstream past Phillips Reservoir and through Sumpter Valley. Groves of black cottonwoods, their yellow leaves seeming almost to glow against a backdrop of blue sky, brighten the river’s banks.

About 25 miles from Baker City, turn right at the well-signed Sumpter junction. Sumpter, three miles farther, sits at an elevation of about 4,400 feet, just into the zone where tamaracks thrive. They often form thickets but occasionally you’ll see a single tree, its orange-tinged branches as conspicuous as a lighthouse amid the unbroken background of green pines and firs.

From Sumpter continue on the byway 15 miles to Granite, your last chance until Haines, another 60 miles or so, to buy a Snickers and a cold soda (or, given October mercurial meteorological tendencies, perhaps a hot mug of coffee).

Stay on the byway, marked as Forest Road 73, following signs to Anthony Lakes. About 10 miles from Granite, and just after the highway crosses the North Fork of the John Day River, continue straight rather than turning right at a sign for Anthony Lakes.

Now you’re driving Forest Road 52, the Blue Mountain Scenic Byway. The road sign says Ukiah.

After a few miles the paved byway bisects Trout Creek Meadows, named for a tributary of the North Fork. Here, stands of aspen, which gleam in their unique shade of yellow, compete for attention with the tamaracks in the deep woods that border the meadows.

Charlie Johnson, a longtime Forest Service ecologist who retired last fall, counts the meadows among his favorite photograph subjects. In particular he likes to aim his camera to the east, putting the colorful foliage in the foreground, with the 9,000-foot Elkhorns in the background.

“A cacophony of color,” Johnson calls the scene.

Turn around at the meadows and reverse your course to the North Fork John Day. Turn left to get back on the Elkhorn Drive, which climbs for a dozen miles to Elkhorn Summit, at 7,392 feet the second-highest point reached by a paved road in Oregon. (The only taller summit, at 7,900 feet, is on the Rim Road at Crater Lake National Park.)

From Elkhorn Summit the byway descends to Anthony Lakes and then to Baker Valley. The highlight along this section are cottonwoods that border the highway. Tamaracks are plentiful, too.

Desert Drive

DESTINATION: Desert country east of Baker City, including the shore of Brownlee Reservoir

DISTANCE: About 130 miles

WHEN TO GO: Now through October

PRIMARY COLOR(S): Scarlet, red and yellow

Who needs trees.

Not Baker County.

The dazzling hues on this trip will force you to squint even when you can’t spot a tree without binoculars.

The stars are shrubs.

For example rabbit brush, a plant so plain for most of the year that it makes even its rangeland companion, the drab gray-green sagebrush, seem vibrant.

But in late summer and early fall rabbit brush bursts into blossoms as yellow as a fleet of New York cabs. You’ll see miles of the stuff as you drive east of Baker City on Ore. Highway 86 (take exit 302 off Interstate 84).

Follow Highway 86 to Richland, about 41 miles from the freeway. In the center of Richland turn right at a sign for Huntington. This is the Snake River Road, and it turns to gravel (relatively smooth gravel, except occasional stretches of teeth-rattling washboard) a few miles from Richland, soon after it crosses the Powder River.

The road climbs to an overlook of Brownlee Reservoir, then plummets, in a serpentine way, almost to the reservoir’s shore.

For the next 30 miles the road remains close to the water, but the sights most likely to snare your eyes are strewn across the steep slopes that rise above the road. The deep red clumps are sumac, a shrub with lance-shaped leaves.

Sumac’s beauty hides a nasty secret, though. Touch the shrub and you might spend the next few days scratching your skin raw and bathing in calamine. Sumac, like poison oak (which also turns a fiery red in autumn), can irritate the skin.

Among the prettier parts of this drive are several coves where tributaries trickle into the reservoir. Trees, which are scarce in this arid land where summer temperatures often surpass 100 degrees, form jungle-like thickets along the moist streamside strips. Common and quite colorful species include scarlet hawthorne, yellow mountain maple and yellow cottonwood.

Johnson said he enjoys trying to capture, on color slides, the contrast between the vivid shades of the leaves and the dull, tawny tans of the surrounding slopes covered with sun-baked bunchgrasses.

The rest of the route, along Interstate 84 from Huntington back to Baker City, parallels for many miles the Burnt River, which is bordered by cottonwoods and willows.