Officers train to handle meth labs

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, May 21, 2002

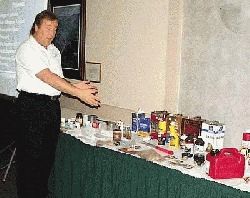

- Charles Stocking, a captain with the Cass County (Mo.) Sheriff's Office, was one of two instructors who taught a two-day course on detecting clandestine meth labs. Here Capt. Stocking points out some of the common ingredients used in cooking meth. The course, which concluded today, was offered at the Sunridge Inn for 45 participants by the Baker City-based Pacific Northwest Law Enforcement Training Center. (Baker City Herald/Kathy Orr).

By MIKE FERGUSON

Trending

Of the Baker City Herald

The twin problems of breaking up and cleaning up after methamphetamine labs has been well documented and publicized.

But for law enforcement officers throughout the Northwest, there’s another critical piece to the puzzle: how do officers take care of their own personal safety while disposing of volatile chemicals and arresting potentially volatile suspected criminals?

Trending

Helping to assure a measure of police officer safety is the purpose of the latest course offering at the Pacific Northwest Law Enforcement Training Center, which sponsored a two-day course for 45 supervisory officers called andquot;Supervising Clandestine Lab Investigations.andquot; The conference concluded this afternoon.

Among the students were three officers from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Vancouver, B.C., where authorities are dealing with the kind of American export they’d rather do without.

andquot;For us (methamphetamine manufacturing is) more of an urban problem than it is (in the U.S.), but it’s definitely growing,andquot; said Sgt. Jerry Prevett, a member of a 40-member drug task force stationed in Vancouver but responsible for enforcement throughout all of British Columbia. andquot;We don’t have this kind of advanced training available beyond our two-week introductory course. And making these contacts with law enforcement in the U.S. is invaluable. The contacts we make, we maintain.andquot;

Those contacts include the two veteran officers teaching the course, who between them have busted up more than 1,100 meth labs.

The two Capt. Charles Stocking of the Cass County (Mo.) Sheriff’s Department and Sgt. Jim Wingo of the Missouri Highway Patrol offered up chilling statistics: on U.S. Forest Service lands, the number of meth labs and dump sites detected increased from 37 and 70, respectively, in 1999, to 214 and 274 in 2000, the last year for which statistics are available.

The federal Drug Enforcement Administration says that during meth lab busts in 2000, officers had to deal with 841 children who lived in the home where the drug was being manufactured.

Federal drug officials estimate there are 356,000 andquot;hardcoreandquot; meth users in the U.S. and about one million users in all.

DEA arrests for meth use or manufacture were up 85 percent between 1996 and 2000.

andquot;For us, officer safety is the biggest concern,andquot; Stocking said during a break in his animated lecture and PowerPoint presentation. andquot;These guys need to be able to teach their officers what they’re getting themselves into (when they break up a manufacturing operation) and what they’ll encounter.

andquot;We’re trained to deal with dangers we can see someone puts a gun to your head. With clandestine lab enforcement, you don’t know the danger because you can’t see it. By the time you realize how dangerous these chemicals and these criminals are, it may be too late.andquot;

According to Stocking, police departments appreciate the advanced training because it’s offered by police who are still providing the service they’re professing in the classroom.

andquot;We see changes in (meth cooking) as they’re happening, and we’re talking to people around the country about the scenarios they see,andquot; he said, adding there are andquot;hundreds and hundreds of waysandquot; and raw materials used to manufacture the drug.

Wingo said the growing meth problem has a toll both on the environment and the people who live where the drug is manufactured or who later purchase the property or vehicle or stay in the hotel room where the manufacture occurred.

andquot;The hazard to the community is obvious, but not so apparent is the effect it has on children and on the environment,andquot; he said. andquot;In Missouri we’ve seen lots of labs set up in national parks and forests, where they simply dump their waste on the property. Here in Oregon you’ve seen a 50 percent increase in the number of labs seized, and those numbers bear out around the country.andquot;

Recently Wingo offered the class in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Police there had no idea about the most common items transported by meth cookers, he said, including hydrogen peroxide, ephedrine, lantern fuel and acetone items that the two teachers displayed prominently during their Baker City appearance, a visual reminder of what officers ought to be looking for during traffic stops.

It didn’t happen during the most recent class, but the two teachers have led classes during which students’ andquot;final examandquot; was to actually cook meth in class. The purpose, Wingo said, is to alert officers to the danger inherent in producing the drug as well as the relative simplicity of the process, andquot;for people who know what they’re doing.andquot;

PNLETC training manager Lana Emery wanted the public to know that aspect of the course is not being offered in Baker City.

With nine training courses down and 10 more to go during the rest of the year, Emery said the courses are getting andquot;maxed out.andquot;

Upcoming courses range from weapons of mass destruction to white collar crime to hostage negotiation.

andquot;We’re seeing a lot of demand, particularly for classes (that are drug related),andquot; she said. andquot;These classes for people who supervise drug task forces are very popular.andquot;